By Shahram Heshmat Ph.D.Science of Choice

Posted Aug 29, 2017 on psychologytoday.com

Everyone is in denial about something. Self-deception, or lying to yourself, is simply a motivated false belief. False beliefs can satisfy important psychological needs of the individual (e.g., confidence in one’s abilities). The following are some of the lies we tell ourselves.

1. Ignorance is bliss.

One of the most difficult problems in sustaining goals is how to persist in the face of negative feedback. Strategic ignorance can help to achieve persistence. How? Avoid information sources that could demotivate you (Benabou and Tirole 2002). For example, someone who says “till death do us part” during the marriage ceremony need not be aware of the divorce statistics.

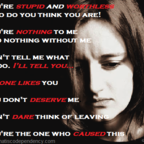

2. Reality denial.

Denial is a psychological defense we all use against external realities to create a false sense of security. Denial can be a protective defense in the face of unbearable news (e.g., cancer diagnosis). In denial, people say to themselves, “This is not happening.” For instance, alcoholics insist they have no drinking problem.

3. Overconfidence.

Overconfident individuals think that they are blessed, that they are well liked by others, and that they’ll come out on top. (As the bumper stickers state: “Jesus loves you, but I’m his favorite.”) For example, 90 percent of all drivers think they are above average, and 94 percent of professors at a large university were found to believe that they are better than the average professor. Unrealistic optimismcan have significant health consequences. Psychologist Loren Nordgren (2009) found that among a group of people trying to quit smoking, the ones who gave especially high ratings to their own willpower were most likely to fail.

4. Self-handicapping.

This behavior could be considered the opposite of overconfidence. If a person is uncertain about her true ability and afraid to find out what her true ability is, she might refrain from doing the work that might reveal her as having a low ability. In such a case, a successful performance could be attributed to skill, while an unsuccessful performance could be externalized as due to the lack of good preparation.

5. How I like myself to be seen.

People like to be perceived favorably, by themselves and by others, but some personality traits that carry a high social value (altruism and fair-mindedness) are not directly observable to outsiders. Our actions, however, offer a window into our personality and tastes (Benabou and Tirole, 2004). For example, giving money to a panhandler, or changing Facebook profile photos to honor the victims of some new tragedy.

6. Cherry-picking data.

People tend to embrace information that supports their beliefs and reject information that contradicts them. For instance, people require more information to accept an undesirable idea than they do for a desirable one.

7. Sour grapes.

In Aesop’s fable, the fox tries hard to get his hands on a tasty vine of grapes, but fails in all of his attempts to acquire the grapes; at which point, the fox convinces himself that he really didn’t want those grapes that badly after all. In the presence of dissonance (awareness of different beliefs), the individual feels psychologically uncomfortable and attempts to reduce it. The motive is to maintain a positive self-image.

8. Me and others.

Psychologists use the term attributions (or causes) for people’s explanations of the events in their lives. We tend to attribute our success to our enduring character traits, and our failures to unfortunate circumstances. For example, when we say, “You failed, because you did not try hard enough; I failed, because I had a headache from staying up all night with my son.” An alcoholic may be happy to tell himself he “just cannot help it” in order to have an excuse for persisting.

The key aspect of these lies is that people treat (or search for) evidence in a motivationally biased way. Self-deception can be like a drug, numbing you from harsh reality, or turning a blind eye to the tough matter of gathering evidence and thinking (Churchland, 2013). As Voltaire commented long ago, “Illusion is the first of all pleasure.”

References

Benabou, R. and Tirole, J. (2004). Willpower and personal rules. Journal of Political Economy, 112(4): 848-886.

Churchland P. (2013) Touching A Nerve. W.W. Norton & Company

Elster J (2009) Explaining Social Behavior: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press

Gloman R et al. (2016) The Preference for Belief Consonance, Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 30, Number 3—Pages 165–188

Nordgren, L. F., Harreveld, F. V., Pligt, J. V. D., (2009) The Restraint Bias: How the Illusion of Self-Restraint Promotes Impulsive Behavior. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1523-1528.

About the Author

Shahram Heshmat, Ph.D., is an associate professor emeritus of health economics of addiction at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

In Print:

Addiction: A Behavioral Economic Perspective

YOU ARE READING

Science of Choice

10 Faulty Thoughts That Occur in Body Dysmorphic Disorder

![By Martin Ransohoff (http://web.poptower.com/tyrel-ventura.htm) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://cdn.psychologytoday.com/sites/default/files/styles/essentials_thumb/public/field_blog_entry_images/2017-09/tyrel_ventura.jpg?itok=gW5L7Y3D&cache=o59u44)

Explaining Delusional Thinking

The Many Ways We Lie to Ourselves

Most Popular

- 1

How to Spot Narcissistic Abuse

- 2

Magnesium and the Brain: The Original Chill Pill

- 3

How Mentally Strong People Respond to Snarky Comments

- 4

3 Ways to Regulate Your Emotions

How to Leave a Toxic Relationship and Still Love Yourself

You Might Also Like